Sant Joan de Boí is the church that preserves the most architectural elements from the first phase of construction that took place in the Vall de Boí in the 11th century.

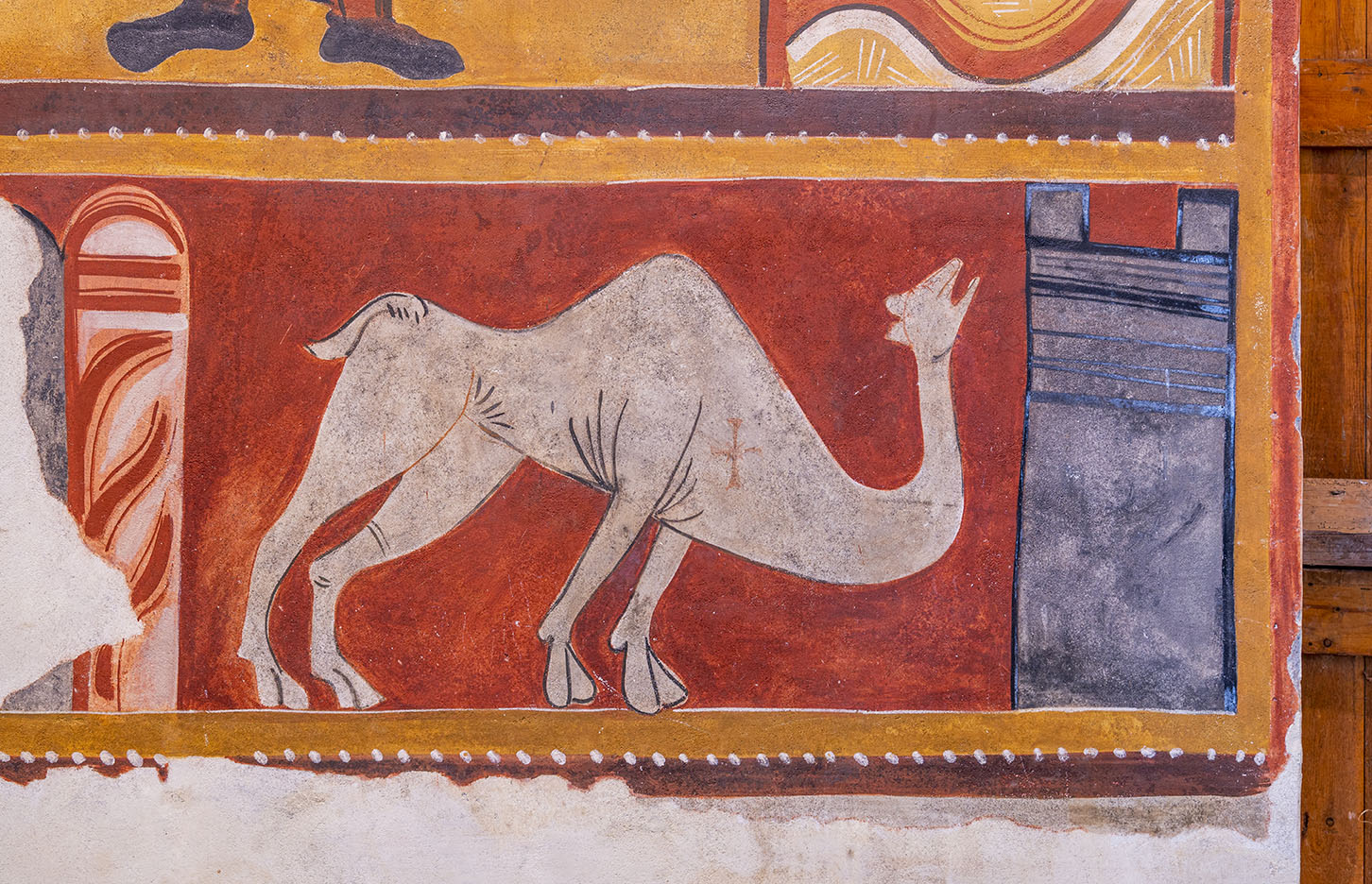

Basilica-shaped (like Sant Climent and Santa Maria de Taüll), Sant Joan de Boí boasts mural paintings decorating the interior of the naves, with scenes such as the Stoning of Saint Stephen, the Minstrels and the Bestiary.

During the latest restoration the aim was to give the church an appearance as similar as possible to what it would have looked like in the early 12th century; the interior was therefore plastered and copies were made of all the fragments of mural paintings currently preserved at the National Museum of Art of Catalonia.

In Sant Joan de Boí you’ll learn more about what role the Romanesque wall paintings played and the original appearance of these churches.